From Lucy Lippard’s Window: Living with Art

In the summer of 2012, I did some research on the Lucy R. Lippard Collection in Santa Fe, New Mexico, while I was staying at the Fieldwork:Marfa residency in Texas. I was interested in movements of withdrawal from the art world ‘centre’, in the way that Donald Judd had effected through his retreat from New York to the desert town of Marfa in the seventies. I found myself drawn to other examples of withdrawal strategies, both contemporary (as explored in Maria Lind’s curatorial research project and exhibition Abstract Possible from 2012, for example), as well as historical (such as the extreme case of artist Lee Lozano’s practice). I ended up focusing on Lucy Lippard (b. 1937), the art writer and curator who moved from New York to the small town of Galisteo in New Mexico in 1992. Here, she set up a local newsletter and started writing books on the history and archeology of the land. It seemed like another way of working, taking her direct environment and the landscape as a starting point, although perhaps it wasn’t all that different from the way she had worked in New York.

.jpeg)

Inside cover of the Sniper's Nest catalogue (1996), displaying objects and trinkets from Lucy Lippard's New York apartment. Photo by Douglas Baz

.jpeg)

Picture from Stuff – Instead of a Memoir (2023), showing a wall and shelf with objects in Lucy Lippard's current house. Photo by Mira Burack

I look around a lot, at what’s on the walls and out the windows, and connect it

with what I’m writing, thinking, or organizing about.

(Lucy Lippard, 1996)

I have long been an appreciator of Lucy’s style of writing about art, which pioneered a more accessible, personal way of practicing art criticism, in which the writer's position is subjectified. She is usually straight to the point, but she also allows for doubts and questions to seep through. In her texts, Lucy often acts as a bridge or a catalyst, from the idea of helping artists communicate with people. She understands art as part of social reality and in direct dialogue with it. In a similar way, her curatorial projects highlighted the work of artists who were interested in the world around them and the political concerns of the time. From 1968 onward, Lucy began to develop her voice as an outspoken feminist writer and curator. She has often described her political engagement and participation in activist groups as a “belated radicalization”, while in fact she was, in so many ways, far ahead of art world developments.

I found out that when Lucy moved to Galisteo in the early nineties, she donated most of the art objects and several other items from her New York apartment to the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe, which is located near where she lives. Her new house was much smaller and had more windows than walls, so she couldn’t bring all her belongings. The more than 300 objects she gave to the museum became the Lucy R. Lippard Collection, although Lucy herself has always called it her “stuff”. I got in touch with museum curator Laura Addison, who told me about the collection, showed me a selection of the works and put me in touch with Lucy. I learned that the collection was first presented in an exhibition called Sniper’s Nest: Art That Has Lived with Lucy R. Lippard, which was curated by Neery Melkonian and made stops at several art institutions throughout the United States between 1995 and 1996.

Lucy Lippard with rock art in the Galisteo basin, 1993. From the Sniper's Nest catalogue

Sniper's Nest: Art That Has Lived

with Lucy R. Lippard catalogue,

Bard College, 1996

I was always saying that I moved to New Mexico to get away from art,

which annoyed my artist friends. Actually, it was the art world I was finally escaping.

Art still means a lot to me. It’s my base but no longer my obsession.

(Lucy Lippard, 2023)

The Sniper’s Nest exhibition presented many of the objects from Lucy’s loft in Lower Manhattan, where she spent “twenty-six emotionally, esthetically, and politically exhilarating years”, as she herself wrote in the exhibition catalogue. During these years, the apartment slowly filled up with artworks given to her by friends. Lucy was not a collector who actively purchased art, but because she was in touch with a lot of artists, it was not uncommon for her to receive a work as a present. Many of her artist-friends became well known figures in the art world. Among the works she received are pieces by Louise Bourgeois, Ana Mendieta, Judy Chicago, Lorna Simpson, Eva Hesse and many others. Most of the artists are of Lucy’s generation, which means that a number of them are no longer around today. Faith Ringgold (1930-2024) and Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith (1940-2025), for example, both passed away recently.

The collection includes several correspondence pieces. There are 197 I Got Up postcards by On Kawara, which he sent to his friends over a long period (in Lucy’s case, the cards were received between 1969 and 1975). There are also postcards from Eleanor Antin’s 100 Boots project (1971-1973). There are two letters written by Joseph Cornell, one from 1967 and the other from 1969, in which Cornell attempts to set up a meeting with Lucy, which never took place. These letters are accompanied by a collage painting and miniature objects, including a yellow feather in a small envelope, coloured rings of different sizes and a king of hearts card. They are typical of the items Cornell imbued with personal meanings and used for his box assemblages. They also reflect something of the intimate nature of the Lucy R. Lippard Collection as a whole.

Other works include several pieces by close friend Sol Lewitt, who had also created a wall drawing in Lucy’s New York apartment; earth works by Michelle Stuart; two large xerox pieces by May Stevens depicting female revolutionary figures Rosa Luxemburg and Lucy Parsons; and a set of watercolours by Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith, from her series Paper Dolls for a Post Columbian World from 1991. Taken together, the works form a small genealogy of the New York art scene from the 1960s up to the 1990s, moving through minimalism, conceptualism, eccentric abstraction (a term Lucy coined), feminism, multiculturalism, identity politics, and site specificity; and in this way, also mapping Lucy’s trajectory of interests.

Eleanor Antin, 100 Boots Move On (Sorrento Valley, California),

offset lithograph postcard, 1972

Every object has its story and part of this story is mine.

This would be a painless way of writing an auto-biography.

(Lucy Lippard, 1996)

In the Sniper’s Nest exhibition catalogue, Lucy describes the collection as “a visual record of friendships, obsessions and political struggles”, which is also a way of emphasizing its biographical constitution. The artworks were witnesses and participants in her life. A table made by Sol Lewitt was used daily, while other works were moved around as new objects arrived and needed space. A fibreglass floorpiece by Bruce Nauman was irreparably destroyed when Lucy’s son rode his tricycle over it. In short, the art was never dealt with in a precious, distanced way; it was in an active relationship with the inhabitants of the apartment.

In addition to the artworks, the collection includes other items from Lucy’s home: posters, books, buttons, rocks and other miscellaneous mementos and objects, such as a boomerang and a wooden figure of a pig. Some of these were presented in the travelling exhibition and were also given to the museum. Lucy must have enjoyed presenting the museum staff with the challenge of these objects that escape regular artwork categories. Most of these items remain uncatalogued. Curator Laura Addison told me, “I think of [the collection] in terms of an interesting ‘problem’ that has no (and needs no) solution. Museums, being taxonomic projects, seem to require a straightforward categorization of each and every object. But from my perspective, the ‘uncategorizables’ are great prompts for us to think about the nature of what we do in museums and the ambiguous nature of the objects we are charged with caring for and, therefore, classifying.” In the Sniper’s Nest catalogue, Susana Torres wrote that she hoped the show would contribute to deconstructing the dominant concept of what constitutes a great collection. The miscellaneous items may play a role in that, as they also function as a kind of unconventional archive that exists alongside the artworks and reflects their owner's wider interests.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Matching Smallpox Suits for All Indian Families After US Gov’t Sent Wagon Loads of Smallpox Infected Blankets to Keep Our Families Warm, from the series Paper Dolls for a Post-Columbian World,

xerographic print with

watercolor and pencil, 1991

Fear No Art button in the Lucy R. Lippard Collection

.jpeg)

Exhibition view of Sniper's Nest: Art That Has Lived with Lucy R. Lippard, at Bard College, October 28–December 22, 1995. Photo by Douglas Baz

.jpeg)

Lucy's collection of tchotchkes, natural objects and political pins, installed in the Sniper's Nest exhibition at Bard College, 1995. Photo by Douglas Baz

I love my accumulations and I wonder what they have to do with my sense of time. I’m against consumerism and spend very little money on things or clothes, but I’m a pack rat and live in a gigantic nest of clutter. I build these nests around me wherever I go, thinking each time that I’ll make this a clean, clear, sparse space, an undistracting environment, and looking around a week later to find it’s disappeared. Like the time to clean it up and start again.

(Lucy Lippard, 1979)

I met Lucy in September 2012 at her house in Galisteo. She lives in a small cabin with big windows that look out onto the high desert landscape of New Mexico. Her house, of course, was filled with art again. She gave me a tour and showed me some of the works. There was a postcard with black circles by Eva Hesse, a photograph by Jack Levine, a Judy Chicago work in the bedroom and much more. All surrounded by family photographs, piles of books and trinkets. She told me about her move to Galisteo and explained that Harmony Hammond, who was in the Heresies collective with her, was the first to move there from New York. In the years after, several other friends followed: May Stevens, Nancy Holt, Caroline Hinkley and Judy Chicago all came to live in the same area. Lucy also talked about getting older and becoming a caretaker for some of her ailing friends.

She was busy working on several books, one of them about the Chaco Canyon (published as Time and Time Again: History, Rephotography, and Preservation in the Chaco World, 2013) and another one “on gravel pits” (published in 2014 as Undermining: A Wild Ride Through Land Use, Politics, and Art in the Changing West). She said that she would love to do a book on artists working with New Mexico history and landscape. It was great to hear about these projects that connect archaeological and geological research with current issues on the preservation of land, indigenous land rights and local history. In her publication Overlay: Contemporary Art and the Art of Prehistory (1983), Lucy had already drawn this long line from prehistoric monuments all the way up to the artistic practices of that time. Once she settled in Galisteo, this interest in traces of distant histories in the landscape intensified and became her main focus. One of the first books she published after her move was The Lure of the Local – Senses of Place in a Multi-centred Society (1997), about place-specific art and “historical narrative as it is written in the landscape or place by the people who live or lived there”.

When we talked about the collection of her “stuff” at the museum, Lucy admitted that she felt a little embarrassed about some of the items she had included in the donation, such as her own sketches and drawings by her son, who is an artist now. She said she “just threw everything at the museum” and maybe it was time to ask for some items back, seeing as the museum isn’t likely to display them, while they have a personal significance for her. She said that if she was ever to write a memoir, as people kept saying she should, it would be through the artworks – through the stories that connect each work to the moments, places and people in her life.

A few years later, that’s exactly what she did. Twenty-five years after the Sniper’s Nest exhibition and the creation of the collection, Lucy wrote Stuff – Instead of a Memoir, published in 2023. In this book, she inventories her current house, from wall to wall, shelf by shelf, describing the story behind each artwork and object. Through these items, she recounts her family history, childhood, her life in New York, the exhibitions she curated and meetings she attended, her activist engagements, the trips she made, her move to New Mexico, her research in Galisteo, and the many artists and friends who crossed her path along the way. This memoir-that-is-not-a-memoir is a complement to the Lucy R. Lippard Collection, because it focuses on her current domestic environment; the works from the New York period are not included. At the same time, it revisits the original proposal of the collection and Sniper's Nest exhibition and makes it more explicit: this time Lucy really tells her life story through the objects.

Lucy R. Lippard, Stuff – Instead of a Memoir, New Village Press, 2023.

I’d like to avoid the fetishism attached to objects and focus on the multiple ways

they have accompanied my life. I guess I’m guilty of dragging these things

into my own orbit, as though they have little meaning outside of what they mean to me.

That’s wrong, of course. They have lives of their own, and when I die, they will go on to have new lives, in different rooms… or dumps.

(Lucy Lippard, 2023)

Lucy also gave the museum a collection of artist books and printed matter with some rare and unique pieces. The artist book format interested Lucy from early on, when it became a prominent medium in the 1960s, as part of artists’ attempts to democratize their work and reach new audiences. She was one the founders of artist bookshop Printed Matter, Inc. (1976) and was involved in several artists book projects, such as the exhibition Vigilance: Artists Books Exploring Strategies for Social Concern, that she organized with Mike Glier at Printed Matter in 1978 and later also presented at Franklin Furnace. Lucy was also the founder of Political Art Documentation/Distribution (PAD/D, 1979), an archive of posters and other printed ephemera produced by socially engaged artists, which was eventually donated to MoMA.

This part of the collection at the New Mexico Museum of Art includes books by Vito Acconci, John Baldessari and many others, but the majority of the authors are women, many of whom were dealing with feminist concerns in their work. Several of the books recuperate or reclaim the stories of ordinary or anonymous women, such as Thea (1979) by Judith Nicolaidis, a book about the artist’s aunt who had to flee Greece. Other family histories appear in Athena Tacha’s Hereditary Study I and II (1970-71), which compare body parts of family members through photo studies; and Mary Clare Powell’s book The Widow (1981), an impression of her mother’s life after she became a widow. Other publications focus on well-known women that are presented as ordinary, such as the typed manuscript of scenes from the life of Cleopatra by Jennifer Bartlett, and Annie Hickman’s booklet about her fictional encounters with Marilyn Monroe, accompanied by collages and drawings.

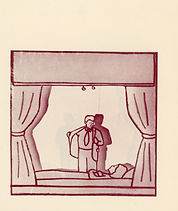

Many feminist artists were concerned with the interplay between personal experience and societal events, and with underlying power dynamics and female agency. A series of small books with cartoon-style illustrations by Ida Applebroog draw us into domestic scenes framed by windows with curtains or blinds. The scenes deal with women’s relationships with themselves and with men, ranging from abusive to loving. The titles of the books, printed in large letters, read as statements uttered by the depicted figures (“I feel sorry for you”; “Sure I’m sure”; “I can’t”), and they are always subtitled “a performance”. Viewing the scenes through windows has the theatrical effect of focusing our attention, but it also defines a limit, a voyeuristic separation between the spectator and the picture. At the same time, it makes us complicit in the scenes and shows that they do not really exist in a private vacuum. These episodes from domestic life are also subject to structures of authority, such as patriarchy, which condition our behaviour and possibilities for expression.

The window as a framing device is used in another way in Carol Condé’s book Her Story (from the Work in Progress project with Karl Beveridge, 1980). Her Story presents a succession of staged photographs of women workers sitting at a desk or table in an interior that reveals something about their social circumstances. In each photo, a large window behind the woman contains a collage insert that situates her in relation to the outside world and in time. For example, one woman sits in her home reading a magazine, while the window insert shows a news photo from the Vietnam war. In another photograph, we see a woman war worker with a view on female Soviet pilots through the window. We can imagine the different relationships these women might have to what is going on outside: the different degrees to which they may be involved in the political context of these events, what part they might play in it, or what could be keeping them inside.

I see the Lucy R. Lippard Collection as a window too, similar to the way Ida Applebroog and Carol Condé used the window in their works as a critical device that makes us aware of our relationship to a wider environment, whether it is by looking ‘in’ or looking ‘out’. The collection is a window that gives us a glimpse into the world of this art writer. It not only encompasses artworks and books, but also other objects from her home, and thereby offers us a view on how Lucy’s personal and professional life are completely tied up with one another. There is a dialogue between inside and outside, personal and political, and the point is that all these categories are blurred and mixed together.

In the Sniper’s Nest catalogue and in conversations, Lucy expressed discomfort with being the centre of attention. She felt that the exhibition and the catalogue essays focused too much on her as a person and not enough on the art. Of course, thinking about the works as part of the collection is only one possible way of approaching them. As Lucy wrote, they have lives of their own, stories of their own to tell, and since they are now integrated in a public collection, they may become part of other narratives as well.

Mary Clare Powell, The Widow, Anaconda Press, 1981.

Ida Applebroog, Sure I'm Sure, from the Dyspepsia Works, self-published, 1979.

Cover and inside view

Two works depicted in the publication Her Story, by Carol Condé, from the Work in Progress project she developed with Karl Beveridge, 1980.

Can we inherit a heretic tradition, I wonder? What is the work of Heresies telling us about authority, and freely giving others authority, about the shifting field of empowerment?

(from the Heresies Box)

Perhaps one of the most precious personal mementos included in the Lucy R. Lippard Collection is the Heresies Box. In 1987, when Lucy left the editorial team of the feminist journal Heresies, of which she had been a founding member since 1977, she received a departing gift from her colleagues. It is a cigar box containing goodbye wishes in the form of 17 cards tied together with a string. Each card was personalized by one of the Heresies members. There is a simple “I Love Lucy” card made by May Stevens. There is a card by Michelle Stuart that folds out to an A4-sized xeroxed image of a feather alongside a handwritten letter with a red wax seal. Sabra Moore created an elaborate fold-out booklet based on her project A Roomful of Mothers, with a text about Lucy’s mother Margaret Isham Cross.

Another card, unsigned, is a typed text that reflects upon a decade of collaboration between the Heresies women who set out to create their own tradition, while attempting to carve out a space in which a variety of voices were encouraged to speak out. It then imagines a future generation of Heresies members who will inherit their legacy and continue the collective’s work. Some years later, in 1993, the Heresies collective disbanded. Lucy told me that they tried to hand over the journal to a younger generation, but it didn’t work and they realized it was time to make room for other initiatives. Around that time, several of the Heresies members moved to New Mexico, where Lucy also ended up. New projects and attachments were created there, as their friendship continued. Now, what remains is the archive of Heresies issues (it is entirely accessible online here), and the Heresies Box as a time capsule that captures that moment.

The Lucy R. Lippard Collection also functions as a time capsule, which may share something with future generations about this writer’s time as an active agent in the New York art scene, when that city was still considered ‘the centre’. Much has happened since then: the art world has gone through many changes and the notion of ‘centres’ and central figures has been further destabilized, though many things continue as before. The collection helps us think about these shifts and the crucial role certain artists and curators, such as Lucy, played in questioning these ideas. It is about art historical time as well as personal time, contained in the meanings given to the works and objects by their former owner and by us in the present moment. In the same way that Lucy focuses on researching the stories behind petroglyphs, rocks and traces in the landscape, we can study the artworks and mementos that once made up the changing environment around this person.

May Stevens, Rosa Luxemburg, verifax and collage with script, 1977

Robert Ryman, Untitled (Birthday Drawing), graphite, chalk and ink on paper, circa 1963

Lorna Simpson, Untitled (Street scene), gelatin silver print, circa 1985

Faith Ringgold, White Lady,

fabric and mixed media, 1976

Ana Mendieta, Rites and Ritual of Initiation, burned grass on paper, 1978

Nancy Spero, Sheela Na Gig, paint, collage and print on paper, 1980

Regina Vater, Untitled, collage of chromogenic and gelatin silver prints, 1984

Michelle Stuart, Brookings Herbarium LXIV, encaustic, pigment, plants, 1988

Sol Lewitt, Hockey Stick, painted wood, 1964

Quotes from:

Lucy R. Lippard, 'New York Times IV' (1979), in: The Pink Glass Swan, The New Press, 1995

Sniper's Nest: Art That Has Lived with Lucy R. Lippard (exhibition catalogue), Bard College, 1996

Lucy R. Lippard, Stuff – Instead of a Memoir, New Village Press, 2023