Rubbing Against the Archive: Caroline Valansi

‘Sensual’ is not a word we usually associate with archives. Archival presentations by artists have become quite common in the last thirty years, and they usually stick to a certain aesthetic, involving vitrines or tables with newspaper clippings, or books and print-outs displayed in an orderly fashion. Whether an artist is working with an existing archive or creating a new collection, whether they are critiquing a claim to authority or bringing to light an unknown history, there is often a solemnness and weight attached to the work which has to do with the archive’s main function of safeguarding knowledge. Yet it is only appropriate that other ideas come to mind when we look at the artworks that Caroline Valansi produced based on her interactions with the archive of street cinemas once run by her family in Rio de Janeiro.

Boca, from the series Peles, 2021. Original posters of pornographic films from the 1970s and 80s and wood, 65 x 95 cm

From the series Corpo Cinético, 2018. Photograph, 90 x 63 cm

Caroline worked with a treasure trove left behind after the closure of the cinemas: film rolls, posters, photos, stamps for newspaper announcements, as well as projection equipment, letter boards and more – materials with such a rich history that it was able to sustain a ten-year research and production period. Some objects were donated to the Cinemateca of the Museu de Arte Moderno do Rio, but everything that remained set off a process of digestion and transformation in Caroline’s practice. She never approached the materials with a revered attitude or treated them as isolated content. Instead, she directly worked with the old film frames and posters in several series, sampling them to produce new drawings or objects. The quantity of the documents – she might have 100 copies of the same poster, for example – allowed her to work through her ideas without being too precious about what she was using. In this way, she was free to formally process the content.

Caroline focused on the pornographic films that occupied the cinema screens from the 1970s on, and the eventual closure of these spaces in the 2010s. She turned her eye especially to the women in pornographic movies in order to explore representations of female desire. The movies are mostly made for the satisfaction of male desire, but she introduced a ‘female gaze’ to them: a gaze that considers women as protagonists in pursuit of their own pleasure. For Caroline, this pursuit isn’t just restricted to a sexual context, but also expands to women’s lives, to their potential in other areas: at work, in the family, in society. It’s about women being able to do what they want: an inevitably political position. The belief in a woman's ability to act freely and seek out pleasure is expressed in her work in direct and celebratory ways. There are sensory, abstract explorations of intimacy and eroticism, and there is sexually explicit imagery and text as well.

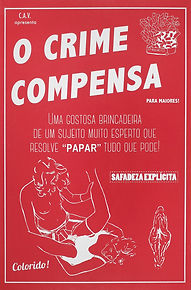

At times Caroline created work that was inspired by the cinema context but also independent of it. For example, she interviewed women online about moral and sexual stereotypes and she collected descriptions of sexual sensations among her friends and acquaintances, which ended up in several works. In fact, many of Caroline’s works go beyond the specific history of the street cinemas and speak much more to the current moment. The Pornográfico Político posters, for instance, are adaptations of original film posters from the 1970s that comment on the recent social-political situation of Brazil. This perhaps explains why curators so often included this series in exhibitions in Rio de Janeiro during the last turbulent political years. It shows that Caroline approaches the street cinema archive from a contemporary and creative desire that considers what these materials mean to us now.

Mulher de princípios (Michele), from the series Boa Para, 2015. Sticker album, 10 x 7 cm (each)

O crime compensa, from the series Pornografia Política, 2015. Silkscreen print, 70 x 50 cm

Cinema Tijuca 1 e 2. Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro, from the series Cinema Também é Templo, 2016. Photograph

We might insist on that question then: what do these materials mean to the artist, and why did she keep returning to these remnants of pornographic representations, when she is clearly an advocate of a more plural, current view on sexuality?

Perhaps there was something else that she discovered in the archive, something that responds to another search that runs parallel to the contemporary pursuit of female sexual agency: a more direct, tangible and affectionate relationship with sexuality represented by the archival materials. The documents that feature in Caroline’s work function in these two ways: they are markers of a friction between antiquated and updated views on sexuality, but at the same time the artist clearly rubbed up against them with much pleasure. There was an enjoyment in the making process of these works that is unmistakable when you look at them. For instance, over the years Caroline returned to the film posters several times, cutting them up, making them into collages, layering them, folding them, reworking them in different ways. The various series that resulted from this appear not so much as a deconstruction or critique, but more as happy love affairs with the material.

From the series Pulsar, 2022. Original posters of pornographic films from the 1970s and 80s, 66 x 50 cm

From the series Cinema Fantasma, 2024-25. Dry embossing on paper painted with mother-of-pearl and phosphorescent ink

To understand this affectionate relation better, I am reminded of another person’s relation to the pornographic street cinemas in Rio. Writer Luís Capucho, a former regular of these theatres, published a book that sets his life story against the backdrop of his visits to Cine Orly in the 1980s. There, in the darkness of the cinema, he met up with other men. By this time, Cine Orly had become a gathering spot for the gay community, albeit a dark and dirty one. The relationship with the cinematic space that Capucho describes in his book is primarily driven by his sexual urges, as he discusses the smells, the movements in that shadowy space, the blown up body parts on the big screen, his sharpened senses. But those sexual experiences are tied up with a great affection for Cine Orly, which becomes the central point around which a queer history of intimacy revolves that is still rarely told.

When Capucho published his homage to Orly in 1999, the pornographic cinemas were already reaching the end of the line. It would only be another decade before Orly and the other street theatres forever closed their doors. The advent of the internet was doing away with the need for such social spaces. Our relationship to sex was quickly and drastically changing, also for those who weren’t into hook-ups. Sexual consumption was becoming less dependent on a specific place and time and beginning to be overabundant on private screens. It was also becoming increasingly commodified, fragmented and alienated. Now sexual content is more available than ever, online. At the same time, studies show that young people are having less sex than previous generations.

Book cover of Cinema Orly, by Luís Capucho, 1999

In this way, we can see that the closure of the pornographic street cinemas is part of our recent history of changing sexual relations. These are complex changes, not yet fully grasped, which have also brought important advancements: for example, there is now a greater collective understanding of consent and more acceptance of plural and fluid gender identities, even if there is still a long way to go. So there is no need to be nostalgic about the past. But two things can be true at the same time and Caroline’s works carry this double load.

After all, an archive doesn’t just preserve knowledge and history, it also preserves feelings. The film rolls, posters and stamps that Caroline encountered give material evidence to the many stories, experiences and feelings attached to the street cinemas, and through her work, they multiply and open up to even more possible readings. Her works invite us to come closer, sometimes as a voyeur, to focus on details, on entangled body parts, sometimes to re-focus, imagine, adjust our eyes. Her works make us look carefully, with attention and affection, to remember that sex is not just a struggle for the fulfilment of one gender or another, but is about a connection with a person, with a place, it’s active and it’s responsive. It’s a potentially transformative act.

2023. Versão em português aqui.

Read a previously written text on Caroline Valansi's work, published in Revista Select, here.